Tales from the Archive

Treatments for Tuberculosis - The Edinburgh Scheme

Tuberculosis (TB) is a highly contagious disease, usually affecting the lungs but which can attack other parts of the body. It is spread through the air by coughing, sneezing or spitting (expectorating).

The world’s first TB dispensary was opened at Bank Street, just off the Royal Mile, Edinburgh by Dr Robert Philip in 1887. It was the central point of what was to become known as the ‘Edinburgh Scheme’ for tackling the prevention, detection and treatment of TB.

Prevention and Detection

There was no known cure for TB at the start of the twentieth century and efforts were instead focused on its detection and prevention. In Philip’s address to the Edinburgh Sanitary Society in 1906, he noted that there were 400 deaths per annum attributed to TB in Edinburgh. Despite this, voluntary notification of the disease had only begun in 1903, and would only become a compulsory measure shortly after his speech. Philip advocated notification of the disease as a key measure in tackling its spread.

The Victoria Dispensary was designed to operate as a ‘uniting point of all agencies’. Located within reach of all who might need it, it became a place of notification and the first point of contact with medical practitioners who could offer advice and treatment. A visiting nurse was sent to each affected home to provide care in situ. Whilst at the home, the nurse could identify others who might well also be infected and arrange for them to receive treatment.

Advice was given on how to prevent the spread of the disease with detailed instructions on where and where not to expectorate and rules on how to clean a consumptive’s room. Given the living conditions of the time, it is hard to imagine that affected households would have been able to adhere to these conditions.

Rules for Consumptive Patients, part 1

Rules for Consumptive Patients, part 2

|

|

Treatment

After presenting themselves at the Dispensary, the patients were classified according to ‘The Edinburgh Scheme’ into three categories: advanced cases, early onset, and cured patients who required further rest to avoid a recurrence of the disease. Advanced cases were sent to a hospital. In 1906, 50 beds had been made available at the City Hospital for these patients where they could be treated in a sanitary environment. Their removal to a hospital was designed to help prevent the spread of the disease to their families with whom they would often share very cramped living conditions.

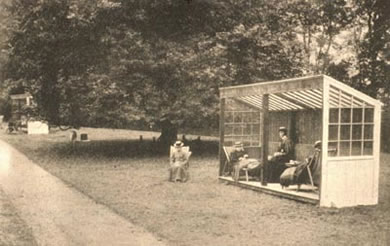

Early onset cases were sent to a sanatorium, such as the Royal Victoria Hospital (originally the Victoria Hospital for Consumption) which was opened in 1894, where they could rest and, in being exposed to lots of sunlight and fresh air, arrest the development of the disease. The three outside walls of the sanatorium consisted largely of windows for this purpose. There were shelters in the grounds where people could spend the day, or for those out-patients, who needed to work during the day, could be occupied at night.

The third part of the scheme, the colonies, were designed to provide work in an environment where recovering and cured TB patients could improve their health. Often, this was not possible in the home environment in which the patient had contracted the disease in the first place. Polton Farm Colony was opened in Midlothian 1910 and patients here could partake in work such as rearing crops and tending to farm animals.

Effects of the Scheme

The death rate from TB in Edinburgh showed a steep decline from 1899 onwards. By 1910 the rate was 1.07 per 1,000, down from 1.9 per 1,000 in 1887 when Dr Robert Philip opened the first dispensary. In 1920, when the full scheme had been in operation for 10 years, the rate had reduced to 0.8 per 1,000. Despite the success of the Scheme in reducing the number of deaths, the Medical Officer for Health, A. Maxwell Williamson, commented that without any way of curing the disease, efforts should remain focused on prevention.

TB Today

Today TB still exists in Britain. According to Scotland’s Department of Health, there are 400 cases per year or a prevalence rate of 7.9 per 100,000 people. An Action Group to combat it was created in 2009. Although there are now effective antibiotics available to treat TB, the advice given by the UK Department of Health remains similar to that advocated by Dr Robert Philip over 100 years ago: “The most important part of controlling TB is identifying and treating those who already have the disease, to shorten their infection and to stop it being passed on to others”.

Image Credits

All images and diagrams are reproduced from the Royal Victoria Hospital Annual Reports (Ref SD3851-3856), with the permission of Special Collections, Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh.LHSA Sources on TB

The following collections are recommended for research into TB using LHSA material:

Edinburgh Royal Victoria & Associated Hospitals Board of Management

Designed by the Learning Technology Section, © The University of Edinburgh